So Close

The distress call sounded sometime after the U.S.S. Goodhue slid past the international dateline. The tiny atoll of Midway — site of the U.S. Navy’s pivotal victory over Imperial Japanese forces two and a half years earlier — lay astern in the night sea. And now, finally, in December 1945, after years of suffering on all sides, the Empire of Japan was defeated and occupied. The Second World War was over. American servicemembers, by the thousands, boarded troop carriers bound for home. Still, hardships and danger remained.

Aboard the Goodhue, newly promoted U.S. Army Sgt. Paul E. Poetter — my father — and more than 1,900 G.I.s and sailors steamed toward the West Coast. “[We] received an S.O.S. from a Liberty Ship with 1,200 veterans on board,” my father wrote in a letter. “This message was picked up by us at 4 a.m. We at once turned around and headed for the stricken ship.” Home would have to wait.

The damaged ship’s last-reported position was 80 perilous miles away. Even at war’s end, the Pacific waters held terrors unknown: mines, wreckage, deadly weather. At 11 a.m., as the Goodhue neared the scene, signal lamps on other rescue ships blinked with Morse Code. “We were only a mile away when they signaled us that we were not needed, so we turned [back] around.” Sgt. Poetter and his mates never learned the outcome of the crisis; all they knew was that the Liberty Ship had struck a floating mine. “It was traveling the same route we had traveled,” my father wrote, a close call he quietly tucked into his letter, penned on Christmas Eve 1945.

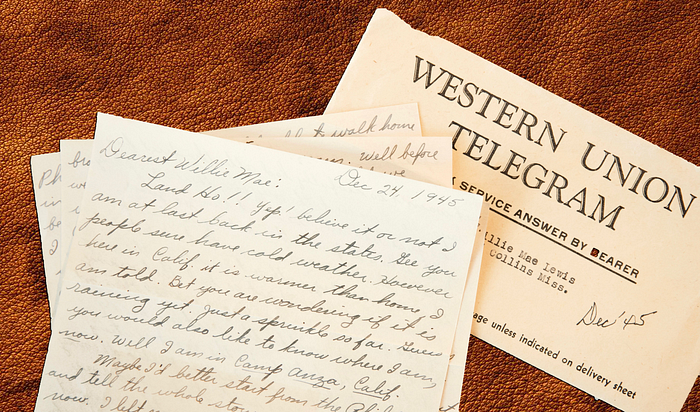

Each December, I hold that dispatch in my hands like a precious pearl. Sgt. Poetter’s words shimmer with subtlety and swirl with suspense — his journey home was as arduous as it was exhilarating. So, too, were the treks of millions of men and women fortunate enough to arrive back safely on our shores. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, Red Cross nurses and doctors — gems all, weathered by sand, salt, and sea — whose legacies we laud, whose fallen comrades we commemorate. My father’s letter, his homecoming story, gleams with the universal hope and gratitude of the Greatest Generation, the spirit of the holiday season, and more than a few wonders.

Aboard the Goodhue, Sgt. Poetter’s journey would prove challenging. He’d boarded the ship in the Philippines on December 6, 1945, after more than two years in the Pacific. Down in Hold №3, he and 147 men crammed onto cots. “It was plenty stuffy and crowded, but no one complained. For this was that day many had been waiting for, for so, so long a time.” Seasickness soon set in, and he battled the ailment for 7,000 miles — the entire voyage. “It wasn’t so awfully bad after the first few days,” he wrote with a shoulder shrug. “No, I wasn’t the only one, there were plenty more just like me.”

Sgt. Poetter was one of “eight million men and women from every service branch, scattered across 55 theaters of war spanning four continents” — according to the National World War II Museum — who would make their way home between September 6, 1945, and September 1, 1946. Dubbed “Operation Magic Carpet,” the effort was the largest-ever combined air- and sealift. And December 1945 was the operation’s busiest month, when almost 700,000 personnel returned to the U.S. “Home alive by ‘45,” the saying went. Everyone everywhere hoped for holiday reunions, a sentiment shared by Sgt. Poetter and Willie Mae Lewis — his sweetheart, my mother.

A year earlier, on Christmas Eve 1944, he’d written to her from Oahu, Hawaii. “Yes, gee whiz, here it is Christmas Eve, yet it is far from seeming that way,” he scribed. “In a letter from home I saw they are having rain and snow and lots of cold weather. Mom is hoping there will be a white Christmas. She always did love the snow.” I imagine my father, a slim figure in sandy fatigues, glancing toward the sky as he penned that line. How impossible snow must have seemed at that moment, on a palm-dotted, sunbaked island. “Willie Mae, I got your nice Christmas card,” he continued. “The picture of the little home sure made me wish I were back in the States. That old homesickness sure gets a fellow about this time of year.” Now, a year later, aboard a cramped troop ship, home was finally on the horizon.

On December 20, 1945, nearing the West Coast, the Goodhue pitched and listed in heavy seas. “That ocean made our boat ride like a roller coaster,” my father wrote. Nearer still, they drifted into a California fog: “It is quite funny to be talking to a guy standing next to you but not being able to see him.” Finally, on December 23, they reached the harbor. With the shore in sight, the Goodhue slowed. On board, the troops received the news: the port was too crowded to dock, and nearby troop encampments were full. A temporary setback.

Soon, they inched toward land — their ship carried several gravely ill patients and had received priority clearance. Ahead in the distance was a tugboat, churning their way. As the tug neared, its name came into focus: Snafu. The boat sported a curious crew — “lots of singing girls and a Santa Claus.” Movie stars, too. “On board and using the loudspeaker was James Cagney.” Lynn Bari and Olivia de Havilland accompanied him. And the Rose Bowl Queen, with court in tow, serenaded the troops with Christmas carols. “No need to say us fellows went for this big!” my father beamed.

A band played as the Goodhue eased into port ahead of Christmas Eve. Red Cross nurses came aboard with newspapers and ice cream. The men delighted in sweet treats and their brush with celebrity as the nurses “took telegrams,” the text messages of yore. Sgt. Poetter dashed off one to his mother and another to Willie Mae; dated “Los Angles Cal 23,” it read: “dearest Landed san Pedro today discharged in Atlanta Merry Xmas loving Paul.”[1]

Much to their surprise, the weary men learned they had one more night’s stay on the Goodhue. As Christmas Eve dawned, they filed off the ship. The Red Cross “gave us ice cold milk (Fresh Milk), the first since leaving the States, and did the boys enjoy it.” They savored doughnuts, too, as they boarded a train to Riverside California — Camp Anza. During the 40-mile trip, Sgt. Poetter marveled at orange groves, dairy cows, and an abandoned airfield. “The most impressive sight was the seemingly never-ending oil wells. The number was beyond counting.” He drank it in, the whole wondrous expanse of America, at once familiar and foreign.

They arrived at Camp Anza to a welcome speech and a “meal of which I have never seen the equal.” “A steak dinner with all the trimmings, including ice cream and a pint of milk. I know I put on five pounds. Ha.” Sgt. Poetter got a haircut; a photographer from Life captured the moment. And the men received “assurance of a speedy homebound train.” Yet, the tracks were silent on Christmas Eve.

Sgt. Poetter slept late on Christmas Day, a “very unaccustomed thing,” given the occasion. “But Christmas was and is a day of surprises for everyone, and for us it was no exception.” They enjoyed a “grand dinner” and delighted in presents made by school children. No train, though, so my father “took in a show.” “The picture: A Walk in the Sun. I thought it very enjoyable.”

No train on the following day, either. Sgt. Poetter documented “anxiety” among the G.I.s. Finally, on his fourth day at Camp Anza, he heard the whistle call. The tracks led east. Closer yet to home.

Today, when I study my father’s correspondence, I’m warmed by his positivity, perseverance, and purposefulness — which I’ve chronicled this year, the 75th anniversary of World War Two’s conclusion. His holiday dispatches, though, are especially poignant. Despite delays and setbacks and near-misses, he made it to Atlanta — HOME! — for New Year’s Eve. He relished presents under the tree, the Rose Bowl on the radio, and unopened letters from his sweetheart. Then, he got to work.

He discharged from the army on January 2, 1946. Took the Civil Service exam two weeks later. Landed a job the next day. Soon, he married my mother and started a family. Eventually founded a university. Built a legacy. Like so many of our Greatest Generation, he advanced with resilience toward his daunting peacetime mission of reinventing himself as a civilian, of creating a new life after war. This Christmas, I feel my dad’s presence so close, and I treasure the qualities of leadership — persistence, forgiveness, resourcefulness, and valor — I learned from his letters written long, long ago. Peace.